When I was growing up, I wasn’t a reader. The only books I remember reading were Oliver Twist and Little Women- the abridged versions. I only read them because they were part of my school’s curriculum.

Later, when I actually started reading, it was because I became interested in a few specific topics. It started with Dawkins, Hitchens and the fellow atheists. Then came history, politics, economics and so on- rendering me a non-fiction man.

I mean, I’ve read some fiction along the way. But by no means am I a proper book worm. In my mind, the only people who can call themselves readers are people who read fiction- those who read simply for pleasure.

From time to time, I force myself to pick up fiction. But the issue I’ve always had is that I cannot hold my attention long enough to complete big books. So, to make sure I have the satisfaction of completing a book, this time, I started looking for short stories or novellas. That’s when a friend suggested I pick up Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Notes from Underground is basically a man ranting about his life and his issues with it—for about a hundred pages. More or less what I do in this blog.

This post, however, is not about the ‘underground man’. I haven’t finished the book yet (obviously).

I’m here because I came across something really interesting. This is the underground man talking about humans and suffering :

“Shower him with all earthly blessings, drown him in a sea of happiness, give him economic prosperity such that he should have nothing else to do but sleep, eat cakes and busy himself with the continuation of his species, and even then, out of sheer ingratitude, sheer spite, man would play you some nasty trick. He would even risk his cakes and would deliberately desire the most fatal rubbish, the most uneconomical absurdity, simply to introduce into all this positive good sense his fatal fantastic element... precisely in order to prove to himself that men still are men and not the keys of a piano.”

I’ve observed that this isn’t just true of humans. It’s true of civilization too—for what is civilization, if not a collection of humans?

Take the West, for instance. After the wars, they more or less solved the big stuff. They built top-tier infrastructure, cleaned up their cities, created efficient markets, and ensured most people had access to comfort and convenience. Utopia adjacent, really.

And then- bored, perhaps, they invented the “culture war.” Now they argue passionately over pronouns, statues, and who gets to bake cakes for whom. These manufactured crises have become so central that they can swing entire elections. And before you know it, you’ve got Mr. Trump—twice.

I should add a disclaimer here: developed nations have reportedly had issues with globalization since the 90s. As manufacturing and other blue collar jobs moved out of West to more economically viable parts of the globe, many people were left with two options: upskill into “better” jobs or get left behind. This shift created a great deal of discontent, which eventually became fuel for strongman leaders to exploit.

See, I have very limited opinion on American politics. But when a self-proclaimed champion of the free market starts pushing policies that could make old-school communists smile- you can’t help but wonder if people or even entire civilizations want to suffer- just to show that they not just keys on a piano, as Fyodor says.

This is the problem with ‘strong man’ leaders. They want to be seen as decisive leaders who can take bold decisions. Interestingly, the quality of those decisions doesn’t seem to matter all that much. I’m talking about the list of tariffs that Trump introduced earlier this month.

I have three things to say on these tariffs.

Globalization is great

The problem these tariffs were supposedly introduced to solve is as follows: America has a huge trade deficit with its trading partners—including India, China, and others. The rationale is that a country must maintain a trade surplus, or at the very least a trade balance, if it wants to prosper. If it has a trade deficit, the story goes, it means the country is being taken for a ride by its trading partners.

Now, is this true? Obviously not. This comes straight out of a 16th-century mercantilist playbook.

Let me repurpose an earlier post.

When country ‘A’ is buying more stuff from country ‘B’ than it is selling to, it means, country ‘A’ has a trade deficit with ‘B’ and country ‘B’ has trade surplus with ‘A’.

Before Ricardo’s time, when mercantilism (read 18th Century Britain) reigned supreme, it was believed that a country must have a trade surplus with every country that it was trading to. It was at this time when works on free trade and globalisation became increasingly popular.

Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage is one such work which helped the world to globalise and thereby increase the scope of even smaller countries to be part of global supply chains.

Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage is simple - each country should produce and export what it is relatively least bad at and import other things from other countries. As [Linda] Yueh puts it - it is in the interests of every country to specialise in terms of what it produces and trade for what it no longer produces as much of. All countries trade globally as international trade increase efficiency for an economy as well as consumption for its people.

It is crazy how this works in the real world. Take the semi-conductor industry for example. The global supply chain is extremely complex such that the mobile / laptop that you are reading this post is made possible because of collaboration from 17 countries (from your chip architecture design to fabrication to assembly and all other raw materials that go into it). This is why globalisation is great.

A small country like Taiwan is at the thick of the global semi-conductor supply chain because it was able to specialise on certain things and integrate itself.

The mercantilist mindset treats trade as a zero-sum game with a fixed pie. But global trade is a positive-sum game. All the value created- measured in the countless human problems it has helped solve- is a testament to just how powerful (and honestly, how cool) globalization can be.

Protectionism makes you non-competitive

Let’s come to something more sinister—the protectionism that tariffs offer.

Tariffs, in theory, are meant to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. But in reality, they often achieve the opposite in the long run. When local companies are shielded from global rivals, they lose the incentive to innovate, cut costs, or improve quality. Why bother evolving when the government is padding your market share?

We in India know this story all too well. Since Independence, India has flirted with protectionism. Initially, it stemmed from a deep distrust of anything foreign—which, to be fair, is understandable after nearly two centuries of colonial rule. But the stagnation that followed was evident. Dubbed the “Hindu rate of growth,” India struggled to innovate or scale its industries.

Then came Mr. Singh, who helped open up the economy in the ’90s and relieved us of our economic miseries. The Indian growth story is one of liberalization and globalization—without which we wouldn’t have been able to bring millions of people out of poverty. And yet, we’re seeing a return of these protectionist tendencies even in India today. Perhaps it's in keeping with the times.

Tariffs create an illusion of strength—propping up industries that would otherwise struggle to survive in a global market. Sure, it might feel like a short-term win: factories reopen, political speeches become easier, and a sense of “taking back control” sets in. But over time, this makes domestic industries fragile and complacent, unable to stand without government crutches. This is econ 101.

Cross the river by feeling the stones

My limited point in all of this is simple: the answer to the complex, deeply rooted challenges of global integration is not to reverse decades of economic consensus on a whim—especially based on half-baked calculations designed to make you look “bold.” One, it doesn’t make you look bold. Two, it creates a whole new set of problems.

Good policymaking isn’t flashy. It’s careful, deliberate, and often boring. Checks and balances isn’t a bug, it is a feature. Steady, consistent decision-making builds trust. And trust is the lifeblood of a functioning economy. Without it, private citizens and companies hesitate to invest, expand, or innovate.

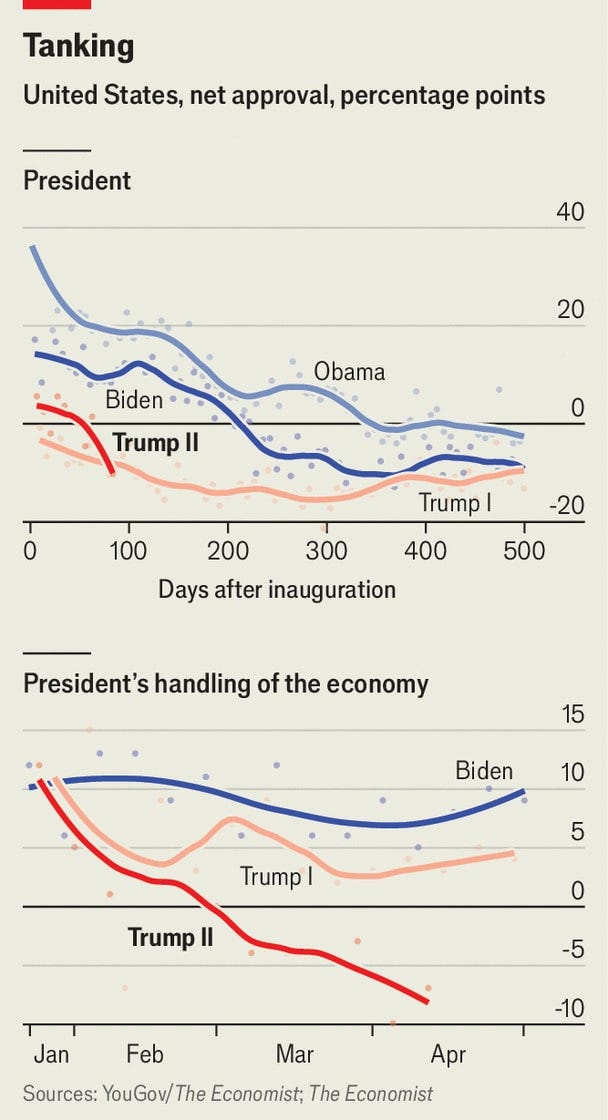

Trump’s declining approval ratings in the wake of erratic decisions are a reminder that policymaking is not theatre. It’s not about looking decisive in press conferences. It’s about building a system where decisions are made with clarity, consultation, and care.

Am I talking about someone closer to home? Nah…

You cross the river by feeling the stones.

That’s all folks. Until Next Time.

Drink Water. Sleep Well.