Weekend in Kanyakumari with Gods, Guns and Missionaries

Reading Manu Pillai amidst the Thiruvizha

The sea sparkled with fireworks, the waves shimmering as they hit the shores. It was a beautiful December evening on the coast of Kanyakumari.

The fireworks were part of the annual feast at Our Lady of Ransom Church in Kanyakumari. The annual feast is a 10-day celebration that is held in December every year. The entire town is brought to a halt these ten days. From road-side shops to music katcheris and Ferris wheel, the whole place is festive. The Church is so deeply woven into the fabric of every family in the town that any attempt to describe the importance of this annual feast would fall short.

The Church and its annual feast (Thiruvizha from now on) feel timeless, as though they’ve always been a part of this town. My mother often shares stories of these celebrations from her childhood. But Christianity in the Indian sub-continent is not that old, at least the kind that is practiced in the fishing villages/towns of Kanyakumari.

Some History

I picked up Manu Pillai’s Gods, Guns and Missionaries only a week before and have been really enjoying it. But it is one thing to read about something and another to see what you are reading, in flesh and blood (intended).

The book charts the history of the modern ‘Hindu’ identity, from an amorphous, fluid set of beliefs to a ‘set in stone’ political philosophy. But that is not the scope of this post. Here, I’m only concerned with what I saw in Kanyakumari.

There have been ‘Christians’ in the sub-continent from the first century. A group called the Nasranis or Syrian Christians as they are also called were apparently converted into the faith by St. Thomas himself. But our story starts only in the 15th-16th century when a certain Portuguese explorer landed in the shores of western India.

The first colonizers, the Portuguese Catholics, made plenty of mistakes driven by their religious fanaticism. It wasn’t just a group of merchants deciding to sail to the subcontinent for trade. These "explorers" were backed by Portuguese aristocrats, armed with guns and a belief that ‘God was on their side’, making victory seem certain.

It’s also important to remember the Protestant Reformation happening in Europe at that time. Catholics despised the Protestant reformers for tearing down idols in Catholic churches and accusing them of being "less Christian" or not Christian enough. This tension in Europe was one of the driving forces behind the Portuguese coming to the subcontinent—not just for commerce, but for religious dominance.

Goa bore the brunt of this zealotry. There were forced conversions, destroyed temples, and, in some cases, temple idols melted down to make chandeliers for churches. Many people fled, some converted, and others lost their lives.

The situation in Tamil Nadu was not that extreme- owing to the fact that the Portuguese were not a major political force here. Missionary work, however was prevalent.

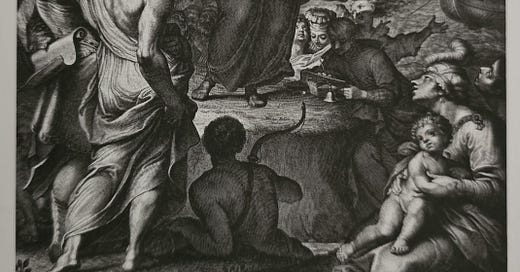

They were convinced that it was up to them to bring the local ‘barbarians’ into the ‘one true faith’. Francis Xavier, one of the earliest missionaries to Tamil Nadu, believed that ‘the native tribes are very well disposed to accept the religion of our Lord Jesus Christ’. In fact, Francis Xavier apparently converted entire villages in one shot. He had announced in a letter that ‘in a space of one month, he [I] made Christians of more than a ten thousand’. But in reality, these conversions seem frivolous. See for yourself:

This elementary lesson (there is one God) having been imparted, he would communicate the sign of the cross and recite a prayer in the local language which he would have learned by heart. Thereafter he gave them articles of the Creed and the ten commandments. When it seemed like the mass of people were ‘sufficiently instructed to receive baptism’, he proceeded with the ceremony and wrote each name (convert’s new name) on a ticket. After a round of destroying idols and bringing in the convert’s families, he bid them goodbye and set off for his next location.

All in half day’s work.

This apparent success was short-lived, as Xavier left after a few years, acknowledging the limitations of his mission. The reality behind many of these conversions was more pragmatic than spiritual. For example, the local fishing community in Kanyakumari, where the annual feast we saw earlier took place, converted to Christianity largely for economic reasons, seeking Portuguese protection against rival fishermen. Conversion, in these cases, was often a matter of survival and economic security rather than a shift in religious belief (at least at that time).

Two Golden Chariots

As the fireworks died down, loud cries erupted from another direction. ‘Sesu Mari Soosai!’ people shouted as they pulled a chariot out of a shed. This was one of two chariots traditionally paraded through the village on the 9th and 10th days of the Thiruvizha. This comparatively smaller chariot housed St. Joseph, father of Jesus while the bigger one, the one with ‘Our Lady of Ransom’ (Mary) made an appearance on the 10th and final day.

The St Joseph chariot procession continued through the night and ended with an early morning mass with the chariot itself as the altar.

Some time later, the main chariot, the one with Mary, was rolled out of the shed to a Latin song which someone had learnt by heart. Both chariots were covered in gold, with the statues wearing gold jewelry and the chariots decorated with gold paper. The main chariot also featured two European knights on horseback, as if protecting the procession.

Men swarmed the chariot as it was being rolled out. Young men seized the chariot’s massive wheels and rolled it onto the streets amid a sea of people. It did not seem like they cared if the wheels might trample their feet; each person was determined to touch and push the chariot as if their life depended on it. The church bells rang.

The chariot procession covered the entire town making multiple stops along the way. People stood in line to wait their turn to see and pray up close with the idols. There was no priest sitting atop the chariot. The volunteers themselves arranged and collected the offerings from the devotees and gave them prasadam in return. Yes, you read that right. After making their offerings—typically coins, fruits, or cash—devotees received lemons, rock salt, peppercorns, bananas, sacred powder (a mix of turmeric and sandalwood), and white threads. The devotees smeared the powder on their heads and wore the white threads on their wrists. All other things were kept sacred beside religious photos and idols back home. The fruits and coconuts that were ‘blessed’ by the chariot were saved to take back home.

If I had not told you about the deity in the chariot, you may have mistook this for a Hindu procession; and you would be forgiven for that. This is all because of how missionaries interacted with the locals.

Assimilation

Early missionaries had no sympathies for the local customs and religious practices. They believed that the local gods (multiple in number) were incarnations of Satan. In fact, in 1510, the Italian missionary Di Varthema, writing about the King of Calicut, described the King as a Pagan, worshipping a "devil" called Deumo. However, the term Deumo is simply a distortion of the Malayalam word deivam, meaning god.

The letters these missionaries sent back to Europe reveal their deeply biased views of local customs. One letter described an Indian deity as a half-man, half-ox creature that drank the blood of precisely 40 virgins. Many letters also recycled exaggerated accounts of sati.

Another letter spoke of thousands of people willingly sacrificing themselves under the wheels of temple chariots (They must come to the Thiruvizha once).

These graphic and sensationalized stereotypes, Manu argues, reflect "more of the writers’ fetishes than an understanding of everyday local realities." Ultimately, these letters were crafted to captivate European readers with vivid, dramatic tales. The missionaries needed to send back stories that would spark curiosity and fascination, keeping their audience engaged.

Over time, the missionaries realized that their initial assumptions—that the local population lacked a sophisticated theological or philosophical tradition and that they are easily convert-able —were fundamentally flawed.

The missionaries eventually started to engage with Hindu texts, trying to understand the local customs. Roberto de Nobili, an Italian missionary needs a mention here. He understood the deeply hierarchical nature of Indian society, recognizing that cultural influence emanated from the Brahmins. Adopting an entirely different approach, he immersed himself in local customs. He dressed like a Hindu ascetic, wore the sacred thread with a cross at the end and adhered to caste practices. He became vegetarian, abstained from dining with others, and funnily even refused to share a meal with a fellow Portuguese missionary who came to visit him.

His strategy was simple yet radical: he convinced people that they could retain their traditional customs while accepting Christ as their God. This approach, in fact, yielded significant results, enabling him to convert in large numbers.

This has always been a defining trait of Indian society: new ideas, particularly religious ones, cannot be cut-copy-pasted directly. They must blend with and adapt to the local customs, becoming deeply intertwined with its fabric. The result is a transformed, localized expression of the religion—unique and unlike anything found elsewhere.

Catholic converts, therefore, preserved many of their ‘old’ customs. Manu describes how Mary is adorned in sarees, goats are sacrificed in churches, and grand chariot processions—like the one we saw earlier—are part of the celebrations. He also references a grant document from a Tamil Nadu church that equates building a church to lighting lamps in one hundred thousand temples and sponsoring Brahmins. By the 19th century, Catholics were even referred to as Hindu-Christians in some contexts.

My Two Cents

One cannot put it more succinctly than Nehru when he famously said that India is like a ‘palimpsest on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed , and yet no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously’. Here, conflicting ideas have often been reconciled rather than eradicated. This rich legacy has shaped a society that thrives on pluralism, even amidst its complexities and contradictions.

Attempting to rigidly define who belongs where based on whether their religion considers the Indian subcontinent its holy land is not only a futile exercise but also an oversimplification of an incredibly layered reality. The interplay of diverse beliefs, traditions, and practices defies singular narratives, revealing a society that has long embraced multiplicity as its strength.

Rather than succumbing to the temptation of drawing boundaries, India’s true essence lies in celebrating its pluralistic nature. It is this pluralism that allows for varied perspectives to coexist, enriching the cultural and spiritual fabric of the nation. Indian pluralism is not a challenge; it is a triumph.

PS:

Go buy Manu Pillai’s Gods, Guns and Missionaries